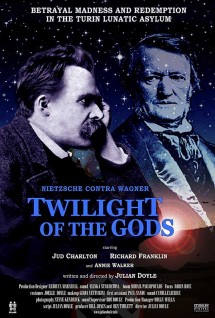

Twilight of the Gods

(Dir. Julian Doyle) (2013)

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), the successor to Schopenhauer and a great writer and weirdo, said he “would never have survived my youth without Wagnerian music.” “And Wagner did become Nietzsche’s awakener, who, by subsequently failing to live up to the youth’s ideals, dealt him wounds which, though they never healed, yet played a salutary role in his development into one of history’s most formidable philosophic writers and thinkers. Like King Ludwig, he at first placed Wagner upon so high a pedestal that the concussion of the idol’s fall shattered not only it but the shocked worshipper, too. Little by little, the youth detected the extent of Wagner’s intellectual and moral charlatanry…”*

P has to make some admissions in reviewing this film. First, one has read Nietzsche and struggled to make head or tail of him, except that his ethic seems to be power-mad, metaphysical hero-worship, and repellent. Where he genuinely strikes new ground, it is in contempt for convention. But he did admire tyrants and he was far more overtly anti-Semitic than the Maestro was. His views were close to what Bertrand Russell called “the mere power-phantasies of an invalid…”**

Second Admission: P finds Richard Wagner to be closest to the mantle of greatest composer of music-drama that ever lived, and though he may well have been an unreconstructed bastard, who the hell cares? The overarching premises of the Nietzsche/Wagner story concern the great musical myths Wagner wrought, and their influence on a precocious but fragile mind. (For example, as Russell noted, Nietzsche’s superman is a lot like Siegfried except that he knows Greek+).

So! We come to a beautiful Sunday afternoon, 20 September 2015, and the Richard Wagner Society SA, that had secured a private screening of Julian Doyle’s psychodrama set in the Turin lunatic asylum – rather incredibly, we understand that the Adelaide Film Festival ‘passed’ on the piece – and it proved to be of definite morbid interest.

Nietzsche (Jud Charlton) has finally gone nuts and we see him, at opening, manacled to his chair in a garret with his wrists disturbingly bandaged. The ghost of Wagner (Richard Franklin) appears and the philosopher cross-questions and confronts the Maestro with charges of anti-Semitism, moral inconsistency, adultery, and so on.

This film is really about Nietzsche, not Wagner: there is a visceral element to the (barely) living man’s accusations and strong hints of self-loathing, guilt and transference. What can you say about a German who writes, in Ecce Homo, “Except for my association with a few artists, above all with Richard Wagner, I have not spent one good hour with a German.”

In the end, the philosopher over-eggs his case and while you feel sorry for his plight, P found himself liking Wagner more. But the close camera work and passionate performances kept one’s interest up over the ninety minutes, and afterwards we had the chance to have brief but interesting speaks with Michael Baldwin who had played Nietzsche in a previous production by the Theatre Guild. Our conclusion: Nietzsche was a flawed, odious but extremely interesting man; Wagner, meanwhile, was a genius, in deathless quest of perfection, which condition absolves nearly all faults and sins.

[*Robert W.Gutman, Richard Wagner – The Man, His Mind, and His Music (1990), p. 315.] [**Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy (1946), p.794.] [+ Ibid, p. 788.]

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments